Remembering My Mother

There are things for which we are never prepared. Childbirth is one of them. The loss of a mother is another. It has been said that, as human beings, there are only three or so significant decisions that we make: whom we marry, whether or not to have children,  where we choose to work and live; each of these decisions narrows the world a little further, concentrating our attention on the work involved in succeeding at any of this. But the death of a mother, I have discovered, unravels those decisions and the accompanying work. It has set me adrift in a place where nothing at all makes sense, where there are no anchors or guarantees, where even the statement, “you are going to be taller than me,” uttered to a daughter at the bus stop this morning, comes with a shadow sentence which tells me, even if I don’t say it aloud, that I can make no promises: of the return of the bus, of the greeting at the door, of years in which she might grow into a height that exceeds my own.

where we choose to work and live; each of these decisions narrows the world a little further, concentrating our attention on the work involved in succeeding at any of this. But the death of a mother, I have discovered, unravels those decisions and the accompanying work. It has set me adrift in a place where nothing at all makes sense, where there are no anchors or guarantees, where even the statement, “you are going to be taller than me,” uttered to a daughter at the bus stop this morning, comes with a shadow sentence which tells me, even if I don’t say it aloud, that I can make no promises: of the return of the bus, of the greeting at the door, of years in which she might grow into a height that exceeds my own.

In an article titled ‘Estrangement,’ in a summer 2008 issue of AARP, the writer, Jamaica Kinkaid articulates her attempt to come to terms with the fact that she stopped speaking to her mother three years before her death. Her effort, however, is not full of regret, but incomprehension that she misses her mother, incomprehension that she does not wish to be buried next to her and, also, does not know if she wishes that her own children be buried beside her someday. She ends with the words, “I do not know, I do not know.”

My life is filled with a similar unknowing. My mother was, as her favorite student described her during his heartfelt and perfect eulogy, difficult. And it was the difficulties that my brothers and I, as adults, responded to, not her ease. I learned to dismiss every concern she brought up, about my brothers, their wives, her grandchildren, me, my life, my father, and her health. Her own regrets and sorrow  were so deep that I feared that I, too, would fall into that bottomless well and never come up for air, or that my affirmation of those sentiments might seal her forever in that tomb of despair. Had I been listening harder, perhaps, I might have heard the mothering behind what she said, might have assumed, rather, the role that she wanted of me, of a gentle and caring child, of the never-grown-up companion I had once been, of being again the girl whose goal in life had been to wear her clothes and do what she did for a living, teaching literature and Greek & Roman Civilization to armies of devoted boys.

were so deep that I feared that I, too, would fall into that bottomless well and never come up for air, or that my affirmation of those sentiments might seal her forever in that tomb of despair. Had I been listening harder, perhaps, I might have heard the mothering behind what she said, might have assumed, rather, the role that she wanted of me, of a gentle and caring child, of the never-grown-up companion I had once been, of being again the girl whose goal in life had been to wear her clothes and do what she did for a living, teaching literature and Greek & Roman Civilization to armies of devoted boys.

Instead I was the opposite of her. I prided myself in taking no shit from anybody. I was flamboyant where she was conservative, boisterous where she was quiet, and forswore the undying affection of school boys and replaced it with the fickle attention of grown men.  I frolicked in the man’s world that had circumscribed her life and I laughed when she spoke of devotion, consistency and simplicity, never letting on that in act though not in word, I was all those things. Whereas she had waited, as refined women of her time did, to have their appearance or clothes or work admired by other people, I paid myself compliments. I wrote about politics when all she cared about was the pride felt in seeing her childrens’ bylines. Somewhere during all those shenanigans I recall seeing both delight and fear in my mother’s eyes.

I frolicked in the man’s world that had circumscribed her life and I laughed when she spoke of devotion, consistency and simplicity, never letting on that in act though not in word, I was all those things. Whereas she had waited, as refined women of her time did, to have their appearance or clothes or work admired by other people, I paid myself compliments. I wrote about politics when all she cared about was the pride felt in seeing her childrens’ bylines. Somewhere during all those shenanigans I recall seeing both delight and fear in my mother’s eyes.  She seemed to both love the cloak of freedom that I had flung so seemingly easily around myself, and feared for my life. I was not a good woman, I was not a good wife. Somewhere down the line, my husband was bound to leave me. Somewhere down the line, I would need something besides flair and flourish and did I have those other, inner resources? I did, I do, but I was not going to let her see those aspects of myself that were so similar to the strengths she possessed. All I would say in response to her “he might leave you,” was, “and if he did I won’t spend my life running after some man who doesn’t want me.”

She seemed to both love the cloak of freedom that I had flung so seemingly easily around myself, and feared for my life. I was not a good woman, I was not a good wife. Somewhere down the line, my husband was bound to leave me. Somewhere down the line, I would need something besides flair and flourish and did I have those other, inner resources? I did, I do, but I was not going to let her see those aspects of myself that were so similar to the strengths she possessed. All I would say in response to her “he might leave you,” was, “and if he did I won’t spend my life running after some man who doesn’t want me.”

In more ways than one, I was trying to define for my mother a life that I wanted her to live. I wanted her to be more like the person I was playing for her.  I wanted to rub away the timidity that overcame her whenever she boarded an airplane to America, the kind of thing that would lead airport officials to fling her bags around and deny her compensation for lost luggage and which I could secure on her behalf with no greater skill than a simple steady glare that would leave her full of awe at powers she believed I had; powers she was glad I had, in this strange, unfriendly, place, but whose acquisition she regretted for, as far as she could tell–and she did tell it!–it had exacted the price of tenderness. I wanted to nullify all of her regrets and fears, to drag her into the future where everything was impossibly hard and yet also possible and full of loveliness. I wanted to put make up on her face, I wanted her to wear the beautiful clothes she owned but never put on, falling back constantly on her worn saris, the old skirt, the tattered nightdress.

I wanted to rub away the timidity that overcame her whenever she boarded an airplane to America, the kind of thing that would lead airport officials to fling her bags around and deny her compensation for lost luggage and which I could secure on her behalf with no greater skill than a simple steady glare that would leave her full of awe at powers she believed I had; powers she was glad I had, in this strange, unfriendly, place, but whose acquisition she regretted for, as far as she could tell–and she did tell it!–it had exacted the price of tenderness. I wanted to nullify all of her regrets and fears, to drag her into the future where everything was impossibly hard and yet also possible and full of loveliness. I wanted to put make up on her face, I wanted her to wear the beautiful clothes she owned but never put on, falling back constantly on her worn saris, the old skirt, the tattered nightdress.

But I held that tattered nightdress to my face a few weeks ago, and breathed in not what it showed to the world – its faded, overused fabric – but the sweet perfume it had earned for itself and still held. My mother’s life was full of a doing with which  mine could never compare. She had no time for the kind of self-creation with which I had become so adept; she was too busy making a living, staving off hopelessness and, more than everything else, helping the people who came looking for her in a ceaseless stream… People who did not care that she wore no make up, that she traveled in buses and scooter-taxis in a country where such travel is perilous even for the young and healthy, that she sometimes opened the door to them with a smile, sometimes – quite often – with a scathing, unfiltered criticism, did not care that her home was an uncertain refuge where sometimes the gate was padlocked, and the phone unanswered and nobody could find her, or that she was awash in eccentricities that lead her to scream for Brand’s Essence of Chicken as though it was a cure certified by the pantheon of multi-origin Gods whom she worshiped, drive her children out of her house “to go live anywhere,” or hang a sign on one of her precious plants

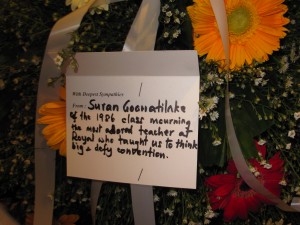

mine could never compare. She had no time for the kind of self-creation with which I had become so adept; she was too busy making a living, staving off hopelessness and, more than everything else, helping the people who came looking for her in a ceaseless stream… People who did not care that she wore no make up, that she traveled in buses and scooter-taxis in a country where such travel is perilous even for the young and healthy, that she sometimes opened the door to them with a smile, sometimes – quite often – with a scathing, unfiltered criticism, did not care that her home was an uncertain refuge where sometimes the gate was padlocked, and the phone unanswered and nobody could find her, or that she was awash in eccentricities that lead her to scream for Brand’s Essence of Chicken as though it was a cure certified by the pantheon of multi-origin Gods whom she worshiped, drive her children out of her house “to go live anywhere,” or hang a sign on one of her precious plants  with the following statement: “We are very poor and we have no money for your religious festivities. If you have any money to spare, please leave some here – Happy Vesak, Happy Christmas, Happy Ramazan, Happy Deevali!” That spirit perfumed her clothes, her hair, her life. It did not make everybody admire her, indeed many people–most specially her students–were terrified of incurring her wrath, but it made them love her and unabashedly. It made them write to her and come and visit her carrying the cakes and sweets she was not supposed to eat, willing to forgive her moods. That spirit frayed her clothes, splashed them with mud, ripped at their seams.

with the following statement: “We are very poor and we have no money for your religious festivities. If you have any money to spare, please leave some here – Happy Vesak, Happy Christmas, Happy Ramazan, Happy Deevali!” That spirit perfumed her clothes, her hair, her life. It did not make everybody admire her, indeed many people–most specially her students–were terrified of incurring her wrath, but it made them love her and unabashedly. It made them write to her and come and visit her carrying the cakes and sweets she was not supposed to eat, willing to forgive her moods. That spirit frayed her clothes, splashed them with mud, ripped at their seams.

Over the course of the two days before she died, my mother had hauled a chair to be mended (so the set could be given to my oldest brother), cleaned her house, given her sister money for an operation, called up all her friends, all her relatives, all her favorite students, and all of our friends, and, of course, secured for herself a bottle of Brand’s Essence of Chicken.  She had given away much of her wardrobe of beautiful, unspoiled saris and dresses, and most of her vast collection of perfumes. Whatever precious jewelry had not already been given away had been robbed. On the day she died, unbeknown to any of us, she was so weak she had to ask the woman who worked for her now and again, to boil water for her and bathe her. On that day, after that bath, she used whatever strength she had left to sit down with one of her students to help her with a college application. She climbed into a car carrying two saris she wanted to give to the servant of the friend who came to pick her up, and spent most of the journey laughing. She suffered a heart attack right as she was trying to field a telephone call from another student’s tennis coach. She left mid-thought, mid-act, mid-goodness.

She had given away much of her wardrobe of beautiful, unspoiled saris and dresses, and most of her vast collection of perfumes. Whatever precious jewelry had not already been given away had been robbed. On the day she died, unbeknown to any of us, she was so weak she had to ask the woman who worked for her now and again, to boil water for her and bathe her. On that day, after that bath, she used whatever strength she had left to sit down with one of her students to help her with a college application. She climbed into a car carrying two saris she wanted to give to the servant of the friend who came to pick her up, and spent most of the journey laughing. She suffered a heart attack right as she was trying to field a telephone call from another student’s tennis coach. She left mid-thought, mid-act, mid-goodness.

I can tell myself a variety of things to stave off the grief that I feel. I can say my brothers were there, their wives were there, she was not alone. I can accept what other people say to me, that a mother does not remember the disappointments, but rather the good times. I can say that she knew, she knew,  that though I did not write and did not call, my inner conversations were always with her, that every time I stood before a crowd, or walked down a street or performed some good work or signed a book, or sang to my daughters, what I felt was her presence, her glad acknowledgement that yes, heaven be praised, he had not left me yet, I was still the most beautiful person in the room, the smartest one, the best, in all things the best. In her absence I will never again be that “best” that she saw whenever she looked at me. In a crowd full of women, in my mother’s eyes, I was always more than any of them. On a shelf full of books, mine was better. My words were articulated more clearly, my clothing was more stylish, my deeds were greater, my husband was perfect, my children flawless. I can tell myself stories but they are as useless as my wearing the cardigan that I had bought for her during her last visit, as futile as my attempt to fill it up with her, to feel her around me.

that though I did not write and did not call, my inner conversations were always with her, that every time I stood before a crowd, or walked down a street or performed some good work or signed a book, or sang to my daughters, what I felt was her presence, her glad acknowledgement that yes, heaven be praised, he had not left me yet, I was still the most beautiful person in the room, the smartest one, the best, in all things the best. In her absence I will never again be that “best” that she saw whenever she looked at me. In a crowd full of women, in my mother’s eyes, I was always more than any of them. On a shelf full of books, mine was better. My words were articulated more clearly, my clothing was more stylish, my deeds were greater, my husband was perfect, my children flawless. I can tell myself stories but they are as useless as my wearing the cardigan that I had bought for her during her last visit, as futile as my attempt to fill it up with her, to feel her around me.

What I remember now is not all the things that I did not affirm in my mother, all the things that I wished she hadn’t done or said, but the things she did do. What I remember is that she brought me music, theater, literature, language, a sense of humor, confidence, strength, joy and a model of motherhood that runs in my veins as naturally as my blood.  I remember that she found it funny when I placed 38th in a class of 40 students and asked flippantly if I had failed math too, as we walked hand in hand away from the Convent I attended. What I remember is that when I was expelled from that convent for an array of irreverences but subsequently invited back, my mother – though she screamed at me in private and threatened to cut off my hair which, she said, was the source of all my problems – dismissed the offer from the nuns and enrolled me in a “school more suited to (her) daughter’s spirit, intelligence and interests.” What I remember is that she paid for piano lessons when we did not yet own a piano, swallowing her pride and letting us go next door to practice. I remember her voice pouring song after song into all of us, bringing Ireland, England and America to us through lyrics and melodies and that those songs still take the edge off the acts of governments that were also discussed in the house. I remember that she polished the floors of our house on her hands and knees with coconut refuse and kerosene and now and then with polish, that she planted every blade of grass in the garden and pruned her lawn and hedges with hand-held shears that left blisters

I remember that she found it funny when I placed 38th in a class of 40 students and asked flippantly if I had failed math too, as we walked hand in hand away from the Convent I attended. What I remember is that when I was expelled from that convent for an array of irreverences but subsequently invited back, my mother – though she screamed at me in private and threatened to cut off my hair which, she said, was the source of all my problems – dismissed the offer from the nuns and enrolled me in a “school more suited to (her) daughter’s spirit, intelligence and interests.” What I remember is that she paid for piano lessons when we did not yet own a piano, swallowing her pride and letting us go next door to practice. I remember her voice pouring song after song into all of us, bringing Ireland, England and America to us through lyrics and melodies and that those songs still take the edge off the acts of governments that were also discussed in the house. I remember that she polished the floors of our house on her hands and knees with coconut refuse and kerosene and now and then with polish, that she planted every blade of grass in the garden and pruned her lawn and hedges with hand-held shears that left blisters  on her piano-playing fingers and that out of the arid earth that surrounded our city home, she could make flowers bloom. I remember that she gave me a girl-only space in a house that held so many permanent and transient visitors, and that it contained a dressing table, a fan, an almirah, a bed, a table, a bookcase, and the silk bedspreads that had once been gifted to her, and that all of these things made my room magical in a time when magic rarely translated into concrete evidence. I remember that she listened to me read, that when I asked her if she was sleeping, the answer even when it took a while for her to say it was, always, a comforting “no, of course I’m not sleeping!” I remember that she encouraged me to wear my hair short and climb our roof and play French Cricket and run faster than the boys and, also, to steal guavas and skip school to attend cricket matches…

on her piano-playing fingers and that out of the arid earth that surrounded our city home, she could make flowers bloom. I remember that she gave me a girl-only space in a house that held so many permanent and transient visitors, and that it contained a dressing table, a fan, an almirah, a bed, a table, a bookcase, and the silk bedspreads that had once been gifted to her, and that all of these things made my room magical in a time when magic rarely translated into concrete evidence. I remember that she listened to me read, that when I asked her if she was sleeping, the answer even when it took a while for her to say it was, always, a comforting “no, of course I’m not sleeping!” I remember that she encouraged me to wear my hair short and climb our roof and play French Cricket and run faster than the boys and, also, to steal guavas and skip school to attend cricket matches…

And I remember that she spent a teacher’s salary on buying bolts of fabric that she stored in a suitcase, beautiful cloth waiting to be turned into dresses by the best of seamstresses according to designs I sketched in ballpoint pen. I remember that except for there being no compromising on decency and modesty, she put no restrictions on the clothes I chose to put on, literally and metaphorically. She stood by and let me be everything that she was not. I wish I had done the same for her.

This is beautiful RU. It brought tears to my eyes and made me realize that I too take my mom for granted.Thank you for writing this beautiful article.It has opened up my eyes and made me think about things I do too..I’m so sorry for your loss ..Words will not take your pain away but time will help you heal.May her soul Rest in Peace..Shiro

This is a lovely post. Thank you for sharing it.

Ruwani, This is so beautiful. I read it and I cried. I can feel your grief. You made her so proud with all that you achieved. Imagine what she could have done if she had the opportunity you had..but you did it for her! She will always be there and your successes will be hers.

Love Angeline

How beautiful Ruvani! All the “firsts” are hard – first month, first birthday, first holiday, etc. The pain and sadness diminishes, but never really goes away, unfortunately. A month after Amma died I was in France and found myself buying lavender for her …

Thank you for sharing this beautifully written piece. I’m thinking of you. Love, Aruni

A wonderful piece to a great lady who made such a mark in my life. She made us (yes the many Children that she had) confident and believe we could face any challenge by the way she taught us and cared for us. There is something of her in every speech I make or whenever I have to pen a few lines for some publication. So she lives ever so proudly in spirit today and for ever. Thank you for this profound piece of skill and warm insight.

Dear Ru, the one that your mother saw, and that inevitably you are.

Losing your mum is like losing a part of yourself that never ever comes back. Keep the good memories strong and try to not have regrets but I know – it’s hard. It was lovely to read this about your mum, I remember her being happy and healthy when I last saw her, many, many years ago.

Take care, keep in touch

Absolutely breath-stoppingly meaningful and beautiful. Yes!! I am in tears….. I guess I am just one of the many who feel with you my friend..

Dear, dear Ru. Beautiful and true.

Dear Ru,

Thank you for wrting something so personal yet universal… it resurrects the momories we cerelessly forget of the best loved times, the loved one we mostly take for granted… ‘my mother’… it is not just your’s, I think it is everybody’s story.

Now, I will stop, think, and act before it is too late.

Thank you, Ru.

Thushara

“The most dementing of all modern sins: the inability to distinguish excellence from success.” — playwright David Hare

Your mother appears to have known and lived this. She had the ability. And so do you.

Sympathies, prayers and thanks —

Clarence

Dear Ru,

Your mother taught me, for a few months at Devi, yet, the impact she made on my life even though during such a short period was tremendous. She gave us the freedom to be ourselves no mater what the world thought…

But most of all from your article I realized why I don’t get on well with my own mother. I want her to be different from the person she is and I guess she wants me to be different too. Knowing this though doesn’t help. No matter how hard I try not to hurt her I always end up doing so. I guess for me too its “I don’t know. I don’t know.

Much love.

What a moving tribute to your mom. Just beautiful.

Beautiful, Akki. Moved me to tears.. & took me back to our A/L class where with the ringing of the bell, she could – in a second – transform from the toughest teacher, to your best buddy. I consider myself luckier than most of her students, as well as her nieces and nephews, since I had the privilege of knowing that the sometimes distant aunt was the coolest teacher on earth, and vice-versa. You never stopped learning from her. In an intangible, indescribable way, she pushed me in the direction that I needed to go – and I will be ever grateful for that.

Ru, so beautiful and eloquent..every word carries a purpose, and every word holds so much love and admiration. The photographs move so well with your words. Thank you for introducing us to your mother, and sharing this relationship. You know that we always think we never did our mothers justice, but mothers have different expectations for their daughters — much simpler than the ones we impose on ourselves.

I am very sorry you lost your mother, Ru, and I know something of how you feel, having lost mine this year, as well. You write very beautifully of the conflicted relationship (I had that, as well.). I keep thinking of the mothers and daughters, various strong women, in A Disobedient Girl, and thinking that your mother got to see this facet of your success where you celebrate the voices of complicated women in a political India. My eyes were moist when I came to the end, but also because of the great pictures you included. Her personality comes through.

Moving tribute, RU.

I am so sorry to hear of your loss.

Dear Ru,

I am so sorry for your loss. This blog entry — indeed, all of your beautiful work — is testament to the part of your mother you keep with you, and I thank you for sharing her with me.

xo

Libby

Hi Ru,

So sorry to hear of your mothers demise and what obviously was an indescribable loss for you- from the Blog. She indeed would have been a proud women to have you as the daughter.

Also a short storey in the reply to the mail you sent. Tke care, Conrad & Aril

Ru,

Thank you for your writing about your mother. I am so sorry for your loss. I hope we can all get together soon.

Be well,

Alice

The year was 1968- 69. She was doing Post graduate study. The seemingly indomitable Indrani Herath I recall from those heady youthful days dismissed all of life’s inherent problems with a laugh.

Deep inside she was the cynic who was defiant of any constraints that wanted to shackle her.

We had great fun laughing at everything and being amused by our own jokes. I remember afternoons when we walked up to Sanghamitta Hall at Peradeniya doubled up with uncontrollable giggles.

She would regularly buy several lottery tickets and assured me she would win big someday. Indrani told me what exactly she wanted to do with her winnings and it was not to indulge. Her ambition was to use it to heal a wounded pride. Inside the bravado was a sensitive, vulnerable, proud human that I have continued to love and remember. I like to believe she has come to terms with what she could not redeem. I can write a thousand lines but I would not able to do justice to her spirit.

Dear Ruvani,

I am so sorry for the loss of your precious mother. What a beautiful piece! Your writing has left me in tears. It brings back such a lot of memories of the stories you used to relate to us about your mum and the antics of her many students at Royal. I feel like racing across the ocean to give my mum a big hug and tell her how much she means to me.

Take Care and God Bless!

Ruveena

Dear Ru,

No better justice to your loss than this moving and complex remembering of your mother. With you I share its conflict, and having my mother still with me, can hope to try to understand her better… Thanks for sharing.

Dear Ru:

I’ve been a very quiet follower of your blog and your wonderful writing but this piece made me want to reach out to you. After my mother passed away the spring of 2008, three and a half years after my father, the first feelings I’ve had besides grief, shock and more shock, have been of envy, whenever anyone talked about their parents. After all, why should I have to listen to how much fun you’re having with them? I don’t want to know someone’s mom’s pickle recipe? Or the fact that they’ll visit you every six months. Or that they’re so irritating or annoying. The fact is, they’re still here, warts and all.

Having no parents or losing a parent, puts you in a club you really don’t want to belong to, and one does retreat into a world of what-ifs and am-i-better-off as well as i-shouldn’t-be-missing-her-so-much. Your words describe these feelings wonderfully and I am so sorry for your loss. Thank you for sharing, because it’s a difficult time, and the more you explore this experience, the more you discover yourself. My thoughts are with you and thank you again.

Madhushree

Ruvani, What a great tribute to your mom, our beloved teacher at Royal. Just like Ranjan Madugalle said, there is something of her in every speech we make, Every letter we write and everytime we help our kids do their grammer homework. Love to your family, Malinda, Arjuna and your father.

Thanks, Ru. What a beautiful tribute to your mother! My mother, too, thought I should wear my hair short, and not only threatened to cut it because it was the source of all my problems, but actually did so one day in a fit of rage. She cut off half my ponytail, and then I had to get on the school bus with the other half intact. But what I really want to say is: our relationships with those we truly, deeply, fiercely love are never simple. I think our mothers understand this.

So touching, Ru. I love the complexities here, which I’m sure you continue to wrestle with. An elegant tribute.

hi,

absolutely enjoyed reading it. I can add so much to this … but dont want to steal your thunder ! never knew you are this amazing writer … person.! So much I could say about you , in the college days ! nothing bad all inspirational ! same about Indrani nanda !

tc

Kosiya

So amazing. I will most certainly get my mother to read this with me, when she visits me later this year.

What could I say Ru? Wonderfull article …. but bearing in mind not the greatest of articles could & would fill her void.

She was one of my greatest teachers at Royal … a champion of many causes …. Teachers who had the inner strength, desire and the courage to strive in making us boys men!

May the good Lord bless her soul and you guys be born as one family … one day!

Take care.

Duwa, many thanks.

I was deeply touched by your comments about mother. They say , “Men don’t cry !” But, I have cried so many times, for so many reasons – some times it was due to self pity and this time it was owing to the candid expressions of a daughter about her mother.

Even though we come from the same family circle, its a pity that I never had the opportunity to be introduced to your mother ; I have been away from S.L. for 40 years and that prevented me from attending many family events. I am glad that I am now closer to your family, your father and the other extended family. By the way Duwa, father gave me a copy of mother’s poems that was published posthumously.

Affectionate best wishes to you and yours,

Uncle Mahinda.

Most mothers appreciate a call from their children on like Mother’s Day.

Grace Frame

click for more info info@annabellelees.com

The year was 1993 in Sri Lanka; I was waiting to meet her for the first time … the elusive “Indrani Miss”! All of a sudden I heard the screeching noise of a chair being shoved and a woman saying “what men, it’s a bucket of a shit”. I thought to myself “SHIT!” as I was next in line to meet her for the first time. Okay, long story short: Years after that we used to share “ratakaju” (one of her favorite indulgences amongst the cup of milk tea where there was more sugar than milk or tea combined) on the veranda of her house and reminisce about our first encounter! She used to say “cheekay, you must have thought who’s this foul mouthed lady”. Whenever I visit Sri Lanka I drive by two houses to remind myself of the wonderful memories of my teenage years: The house I grew up in and Indrani Miss’s house where I used to spend hours talking to her on the veranda eating ratakaju and drinking sugar with milk and tea!

What a lovely memory you have shared. I can picture it all. Thank you for bringing her back to me in this way.

this i read off and on. always makes me cry.

It is a sorrow that never leaves, not even for a second of any day, it’s just that sometimes we stop and let it overwhelm.