Bread Loaf Writers

I check email religiously throughout the day, but my most fervorful check of all is the first of the morning. Early. And today, instead of the usual culling of pieces of information and shards of news that cut like unswept glass underfoot, I came across the brilliance of three friends, all of whom I’d met over a couple of spirit drenched summers in Ripton, Vermont, at the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference.

I check email religiously throughout the day, but my most fervorful check of all is the first of the morning. Early. And today, instead of the usual culling of pieces of information and shards of news that cut like unswept glass underfoot, I came across the brilliance of three friends, all of whom I’d met over a couple of spirit drenched summers in Ripton, Vermont, at the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference.

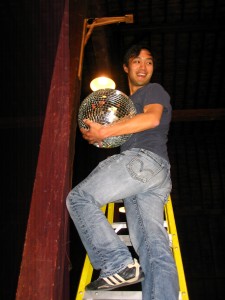

I’ve never been enrolled in a writing program so unlike many of my friends, I had no automatic community of writers to support me or to look up to other than those whom I found in hardcover. And while I would not undermine the value of those, more silent and more solitary companions, I have to say that discovering the “real live” at Bread Loaf was the antidote to my writerly misery.  It has been an unmitigated pleasure therefore to see the people who donned an apron and metamorphosed into waiters in the dining halls each morning, noon and night, or helped lug giant trays of baked brie across the lawns at Treman, or even hang up mirrored balls and tap beer, reap the accolades that are reserved for the most honest writers, the ones who dig deep, spare nothing and give us the stories that carry us all forward along the path to distilling human experience into something worth keeping.

It has been an unmitigated pleasure therefore to see the people who donned an apron and metamorphosed into waiters in the dining halls each morning, noon and night, or helped lug giant trays of baked brie across the lawns at Treman, or even hang up mirrored balls and tap beer, reap the accolades that are reserved for the most honest writers, the ones who dig deep, spare nothing and give us the stories that carry us all forward along the path to distilling human experience into something worth keeping.

Among them – and thank you, gmail, thank you Facebook – I ran into Justin Torres,  writing about truth and fiction and family, that eternal triumvirate of powers at whose feet we writers supplicate hourly hurling word after word in prayer and curse. Here’s an excerpt:

writing about truth and fiction and family, that eternal triumvirate of powers at whose feet we writers supplicate hourly hurling word after word in prayer and curse. Here’s an excerpt:

My parents never lied to us, but damn if they didn’t bullshit us, damn if they didn’t create fiction. My mother mainly relied on guilt, my father used threats, but beyond the guilt, beyond the threats, implicit in all the stories they told us about our betrayals and about the dangerous consequences that awaited us were we not careful—implicit, was the possibility of redemption. My parents were expert at telling two stories simultaneously, one to scare or shame us into subservience, but another was instructive—we listened to find out how we could be saved from our past transgressions, or our punitive futures. In my opinion, good fiction accomplishes this as well, tells the story of our human suffering, and teaches how to do so with charm and grace.

And then, even as I sat there marveling at the way in which Justin had captured not just his life but mine, not simply his brothers and his parents but my brothers and my parents, and both our muses, even as I wanted to linger there, but felt inspired to return to my own writing – but not before I shared his reflection with my father and brothers! – I recognized a second name: Josh Weil. Here is Josh, writing about the trajectory he took to make peace with the tussle between brevity and length, between choking and breathing:

We’ve all been there: a moment when something of such import happens that the space life allows for it seems too small. For me, the time my father told me he had leukemia was like that. The time I came home to an empty apartment and knew my marriage was over was like that. But so were the few seconds—at the end of ten years, of three attempts at novels, of a whole adulthood of trying—when my agent told me that I had finally sold my first book.

I went in search of these friends, to thank them for their work, to share their intelligence with others. And between pauses to write on their walls and tell the world what was “on my mind,” I had the good fortune to stumble upon Reginald Dwayne Betts. The last time I saw Dwayne, he was dancing in the venerable and curiously transformative barn at Bread Loaf.  It was the end of weeks during which we had worked together, discussed writing, life – including life in prison – relationships, futures. This is an excerpt from Dwayne talking on NPR.

It was the end of weeks during which we had worked together, discussed writing, life – including life in prison – relationships, futures. This is an excerpt from Dwayne talking on NPR.

For the first four to six years, no matter where I went, I was the youngest person in the block. If I marked an adolescent shift, it was when somebody younger than me asked me for some advice. That’s when I realized that I was basically growing up in a jail cell. I have all of these memories that have replaced the adolescent markers: I was in a cell below someone who beat a man to death. And I remember guards carrying the dead prisoner on a gurney, the nurses pushing him down the walkway, banging on his chest, trying to revive him. The thing is, what are you gonna do with all the memories you have once you get home? That’s the question posed to all the young people who get sent to prison. Because you will accumulate these memories, and a lot of them won’t be good.

Somewhere in each others’ words, there is resolution for each of them and for me. I realize that I could have read what they have written, or heard them speak, and be adequately moved by their wisdom, even if I had never met them. But to know them as people who find themselves unable to resist the call of the written word, and to have witnessed the camaraderie that comes from experiencing their particular embodiment of that desire at Bread Loaf, this makes all the difference.

I cannot wait to see what beauty this summer will bring.

Wonderful!! Bread Loaf is such an incredible, magical place.

Ru, You Rule. Love you. Charles

Ru,

Thanks for mentioning me. I get to be in the same place with you and Justin, I must have done something kind for someone in this life.