On War? Ask Komunyakaa & Youssef

I was listening to NPR’s morning edition in my car a couple of days ago when a segment on Iraq and Afghanistan came on. It began this way:

The U.S. has officially ended its combat mission in Iraq, while tens of thousands of extra U.S. troops deployed to Afghanistan are moving into place — and so are their top leaders.

Many of the U.S. military officers who fought in Iraq are now taking charge in Afghanistan, and they bring with them the lessons they learned from Iraq. But the lessons can be both useful and dangerous.

As I listened to the various “experts” (Leslie Gelb, president emeritus of the Council on Foreign Relations, for instance, whose many claims to fame include taking up the position that Israel was right to board the flotilla carrying humanitarian aid to Gaza and Michael O’Hanlon of the Brookings Institution whose own credits include describing homosexuality as “an alternative lifestyle” as he talks about the repealing of the DADT policy in the military) about the possibility of replicating what was done in Iraq – through “surges,” “awakenings” etc. etc. – in Afghanistan, it seemed improbable to me that nobody would mention the injustice of the original invasion of Iraq. It is almost as though American journalists and pundits alike have decided, unanimously, to parrot slogans about all that has been done to “fix” Iraq without mentioning who broke it in the first place.

Here’s a gem from Stephen Biddle, a defense analyst who has advised the U.S. Government, no less:

“The Awakening without the surge would have died under an al-Qaida counterattack,” he said. “The surge without the Awakening wouldn’t have been nearly large enough to suffocate an insurgency the size of Iraq’s. It was the two coming together that made the difference.”

Made the difference to what and to whom, exactly?

And here’s one from Michael O’Hanlon who apparently feels that Patraeus and his team “are better off having had to tackle something similar in Iraq.” Because, he says, “They’re not trying to over-learn the lessons of Iraq, but it has to be giving them a certain amount of confidence that this is at least potentially doable.”

Meanwhile, 1,875 people are joining the movement to subversively move Tony Blair’s memoirs to the crime section in bookstores.

In a recent article, Sri Lankan journalist Malinda Seneviratne discusses the decision by President Obama to return the Bust of Churchill that had been left behind in the Oval Office by his predecessor, and the value of such a gesture, undertaken to honor the President’s grandfather, Hussein Onyango, who was tortured by Churchill’s crew, when American-directed abominations continue unabated in Pakistan, Afghanistan and, yes, Iraq. If a dishonorable war is begun we can rest assured that it will end without honor. But if a dishonorable war is inherited by a man a good many of us believe is honorable, should we not expect that it would end both swiftly and with honor?

And, so, I’m compelled to ask, what lessons, exactly, and, better still, what similarities and what potential? Canadians – although there are many who share physical characteristics and language with Americans – are not Americans, and Mexicans – though they relinquish and reclaim the same borders – are not Americans. Afghans are not Iraqis. Sri Lanka is not Israel. Pakistan is not Burma. Bolivia is not Chile. Uganda is not Tanzania. You get the point.

The New York Times provides us with a kind of answer, though even her editors bury the discussion in the Middle East section as though the issue is not one of national importance, particularly in the aftermath of an address to the nation by the President on war and its seeming ebbs and escalations, in an article written by Anthony Shadid (you can find many other articles about Iraq written by Shahid at this link and they provide the perspective that is lacking from the discussion). The article is titled, ‘Restoring Names to War’s Unknown Casualties,’ and follows the journey of a single Iraqi family, lead by Hamid Jassem, to find the location where his brother who disappeared might be buried. He identifies his face as that of #5061 among all those others noted as majhoul or unknown, at the morgue in Baghdad where four screens run through photographs of corpses. Shadid writes:

“The horror of this war is its numbers, frozen in the portraits at the morgue: an infant’s eyes sealed shut and a woman’s hair combed in blood and ash. “Files tossed on the shelves,” a policeman called the dead, and that very anonymity lends itself to the war’s name here — al-ahdath, or the events.

On the charts that the American military provides, those numbers are seen as success, from nearly 4,000 dead in one month in 2006 to the few hundred today. The Interior Ministry offers its own toll of war — 72,124 since 2003, a number too precise to be true. At the morgue, more than 20,000 of the dead, which even sober estimates suggest total 100,000 or more, are still unidentified.

This number had a name, though.

No. 5061 was Muhammad Jassem Bouhan al-Izzawi, father, son and brother.

It is a truism that naming the nameless is what makes the faceless human. It provides the humanity that Amitava Kumar describes in his timely article in Vanity Fair, ‘The Ground Zero Mosque’s Missing Muslims.’ But how do Americans muster that degree of compassion for their Iraqi and Afghan counterparts when they not only remain nameless but the nation’s gatekeepers of the news refuses to acknowledge the injustice that brought us to this moment?

At one moment during his search for his brother’s remains, we have this: “Let me be honest,” Hamid said, flashing rare anger at no one in particular. “Just to tell the truth. It would have been better if we had stayed under Saddam Hussein.” I wonder if that message has been heard within the walls of the Brookings Institute, the CFR, the Oval Office, the audio and visual press rooms littering America’s landscape. I wonder into what column that message would fall: lessons learned? similarities? potential?

I seek truth not in newspapers but in literature. And so I leave you with these two poems written in and of a time of war, a time, it seems, that is with us for life. They are written by one of America’s greatest poets and one of Iraq’s. The similarity of their first and last names is but an accident of fortune.

Facing It

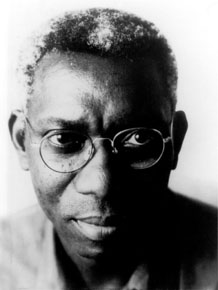

by Yusef Komunyakaa

My black face fades,

hiding inside the black granite.

I said I wouldn’t,

dammit: No tears. I’m stone. I’m flesh.

My clouded reflection eyes me

like a bird of prey, the profile of night

slanted against morning. I turn

this way–the stone lets me go.

I turn that way–I’m inside

the Vietnam Veterans Memorial

again, depending on the light

to make a difference.

I go down the 58,022 names,

half-expecting to find

my own in letters like smoke.

I touch the name Andrew Johnson;

I see the booby trap’s white flash.

Names shimmer on a woman’s blouse

but when she walks away

the names stay on the wall.

Brushstrokes flash, a red bird’s

wings cutting across my stare.

The sky. A plane in the sky.

A white vet’s image floats

closer to me, then his pale eyes

look through mine. I’m a window.

He’s lost his right arm

inside the stone. In the black mirror

a woman’s trying to erase names:

No, she’s brushing a boy’s hair.

from America, America

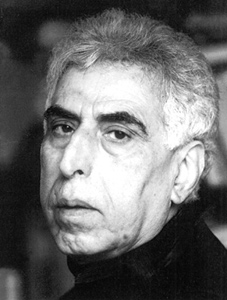

by Saadi Youssef

I too love jeans and jazz and Treasure Island

and John Silver’s parrot and the balconies of New Orleans.

I love Mark Twain and the Mississippi steamboats and Abraham Lincoln’s dogs.

I love the fields of wheat and corn and the smell of Virginia tobacco.

But I am not American.

Is that enough for the Phantom pilot to turn me back to the stone age?

. . .

America:

let’s exchange gifts. Take your smuggled cigarettes

and give us potatoes.

Take James Bond’s golden pistol

and give us Marilyn Monroe’s giggle.

Take the heroin syringe under the tree

and give us vaccines.

Take your blueprints for model penitentiaries

and give us village homes.

Take the books of your missionaries

and give us paper for poems to defame you.

Take what you do not have

and give us what we have.

Take the stripes of your flag

and give us the stars.

Take the Afghani Mujahideen beard

and give us Walt Whitman’s beard filled with

butterflies.

Take Saddam Hussein

and give us Abraham Lincoln

or give us no one.

. . .

We are not hostages, America

and your soldiers are not God’s soldiers …

We are the poor ones, ours is the earth of the drowned gods,

the gods of bulls

the gods of fires

the gods of sorrows that intertwine clay and

blood in a song…

We are the poor, ours is the god of the poor

who emerges out of farmers’ ribs

hungry

and bright,

and raises heads up high…

America, we are the dead.

Let your soldiers come.

Whoever kills a man, let him resurrect him.

We are the drowned ones, dear lady.

We are the drowned.

Let the water come.

(translated from the Arabic by Khaled Mattawa)

Beautifullly written, compelling, moving. I shall share this with a group of “intellectual” hard scientists in USA and Sri Lanka now, and perhaps with Pugwash later. Meanwhile, thank you very much.

Addendum: This piece by Alex Pareene in Salon.com ‘s blog War Room also talks about the insanity of our current media.

http://www.salon.com/news/politics/war_room/index.html?story=/politics/war_room/2010/09/03/bush_obama_bffs&source=newsletter&utm_source=contactology&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=Salon_Daily%20Newsletter%20%28Not%20Premium%29_7_30_110

Nice videos my latest blog post

Noisesurfer Nocturnal Waves https://mashable.carbodyrepairsbolton.co.uk/79.html Johann Sebastian Bach Collection